Nongoloza: king of the Ninevites

- lucilledavie

- Jan 9, 2008

- 13 min read

It all started with a horse back in 1886 - a horse that went missing and had to be found or paid for by somebody. That somebody was Nongoloza, and he felt he was being treated badly, so badly that he moved from KwaZulu-Natal to Johannesburg, where he started his career as a crime king.

"On informing my master of this [the missing horse] he accused me of being negligent and blamed me for it and told me to go and look for it," recounted Nongoloza in a statement many years later. "I told him that as I was working in the garden on that day he could not hold me responsible for the loss, as all the horses were out grazing alone."

Nongoloza described how his "master" threatened to put him jail if he didn't go and look for the horse, so he went and looked but did not find the horse.

"He [Tom J] then told me to go back to my kraal and work for Mr Tom P again, and added that Tom P would then bring to him the value of the horse that was lost. This amount would represent my wages for about two years."

It was this act that set Nongoloza on a very different path from the one he might have taken as "houseboy" or horse groom or gardener, jobs he was doing when the horse went astray.

Nongoloza, a powerful personality, became more famous and enduring than he would ever have imagined, and his legacy lives on more than 140 years later, particularly in the prisons of the Western Cape. He resisted becoming part of the labour-repressive institutions of a rapidly industrialising Johannesburg, like mine compounds, pass laws and prisons, that greeted blacks who were pushed off the land and forced to sell their labour in the towns.

Born in Zululand

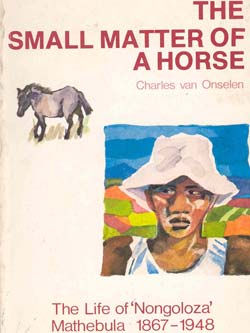

Nongoloza, or Mzuzephi Mathebula, was born in Zululand in 1867 into a family of three boys and two girls. His name, Mzuzephi, means "Where did you find him?" records Charles van Onselen in The small matter of a horse - the life of 'Nongoloza' Mathebula, 1867-1948.

His father soon moved the family to live on a farm near Bergville in KwaZulu-Natal, close to where the Tugela River flows out of the Drakensberg mountains. He grew up herding his father's cattle and living a solitary existence, not being close to his siblings or his father, who was often away from home.

At the age of 16 he got a job as a gardener in Harrismith, some 50 kilometres to the north. He also trained and worked as a groom in the Free State town, receiving a gift of a horse in "part payment for his conscientious labour".

In 1886, at the age of 19, Mzuzephi went to work for Tom J again, not as a gardener as he had done previously but now principally as a groom. It's at this point that the horse went astray, and Mzuzephi was sent to find it.

He went back to work for Tom P, as he was told to do, and was sent to Johannesburg, transporting sugar and flour to the town and returning with empty wagons. He was obviously mulling over his situation - on his return he approached his brother, asking his advice.

"On returning I asked my brother whether it was the law, and whether he thought it fair that I should work and have my wages kept back to pay for the horse which I did not lose," he wrote in his statement. "He told me that I must work or they would put me in gaol and added that he did not want to see me there."

Mzuzephi's deep sense of injustice at his punishment is evident. "I told him that I would not work to pay for what I did not lose and that when I was sent to Johannesburg again I would remain there."

This he duly did, finding work in Jeppe as a "houseboy". He sent home money to his mother with men who lived near his homestead. One of his brothers turned up in Joburg and pressured him to return home to resolve the problem as the family was still dependent on the goodwill of Tom P, on whose farm they lived in return for giving him their labour.

Mzuzephi was reluctant to do this, and resolved to do the only thing open to him under the circumstances: cut all ties with his family.

He dropped his job and took on a new name: Jan Note. The name appears to be a combination of Afrikaans and English words, but, says Van Onselen, "unotha" refers to "native hemp, cannabis, satwa of the best quality", a reference to a dependency that Mzuzephi had developed as a young herdboy.

A groom with four gentlemen

With his new identity he took a job as a groom with "four gentlemen" in a remote house in Turffontein. He was paid very well - 30 shillings a week - on condition he was honest and did not invite any friends on to the property.

Then Note discovered something unusual about his employers. "Purely by chance, Note had taken up employment with one of the many gangs of highway robbers which thrived amidst the unsettled conditions which accompanied the birth of Johannesburg," says Van Onselen.

Within a few months Note was invited to come along on one of the trips. "We had ridden as far as Jukschy River where we dismounted, and I was told to look after the horses," he records. "A coach was coming towards us, and the men pretended to be busy examining their horses' feet until the coach came up to us. The men then held up the driver of the coach with revolvers and some of them mounted the coach and threw all the boxes and trunks belonging to the passengers into the road. These were broken open and searched and all valuables and money taken by the four men."

It didn't take the wily Note long to figure out that this was an easy means of making a living. "Until this time I did not know what robbery was and I was surprised to learn how easy it was to get money by this means."

It wasn't long before he made a crucial decision. "Learning from my experiences with these four men how easy it was to get money by means of robbery, I decided to start of band of robbers on my own, which I eventually did."

In early 1890 he made contact with two men in the black underworld, and set up a base in the rocky overhangs of the Klipriversberg hills 10 kilometres south of the town.

Within a year or two a small community of about 200 men and women vagrants and petty thieves had established themselves in the hills.

And then the leader of this group, Nohlopa, was caught and spent some time in jail, where he learned to read and write, spending his time studying the bible. When he returned he said he was going to drop out and preach the word of God. This decision gave Note the opportunity to take control of the gang of thieves, finally revealing his true genius.

The king and his army

He reshaped the motley band of robbers into a miniature army, what Van Onselen refers to in New Nineveh as the "Witwatersrand's lumpenproletarian army", appointing himself as Inkoos Nkulu or king. "Then I had an Induna Inkulu, styled lord and corresponding to the governor-general. Then I had another lord who was looked upon as father of us all and styled Nonsala. Then I had my government who were known by numbers, number one to number four. I also had my fighting general on the model of the boer vecht generaal. The administration of justice was confided to a judge for serious causes and a landdrost for petty cases. The medical side was entrusted to a chief doctor or inyanga."

He also appointed colonels, captains, sergeant-majors and sergeants in charge. "This re-organisation took place in the hills of Johannesburg several years before the 1899 war was dreamed of."

Note then decided on a name for "my gang of robbers". He wrote: "I read in the Bible about the great state Nineveh which rebelled against the Lord and I selected that name for my gang as rebels against the government's law." They were called the Ninevites or Umkosi Wezintaba - the Regiment of the Hills.

And so, says Van Onselen, the Ninevites emerged as a "tightly structured organisation" with a "certain amount of ideological cohesion and social purpose".

Then Note made another move to consolidate his empire. He banished the women living in the hills, attributing venereal diseases among his men to them. His inyangas were unable to clear his men of the diseases so this seemed the next obvious step. The older men were to take the younger men as "boy-wives", he decreed.

Van Onselen records that to some extent the Ninevites were involved in "social justice", redressing any injustices that fellow black workers experienced at the hands of their white employers.

Prison sentence and prison justice

In April 1900, Note was sentenced to seven years with hard labour and 30 lashes on attempted murder charges. He was sent to Pretoria, where "for the better part of the next seven years, he and his followers entered into an open confrontation with the brutal system of prison administration presided over by Lord Milner and his reconstruction government", according to Van Onselen.

But through it all Note maintained control of the Ninevites and their activities inside and outside of prison. Ironically, this was aided by the Milner government's extension of the pass system, which meant that men moved in and out of the prisons on pass offences, neatly aiding his communication with the outside world. And secondly, because the government did not separate hardened criminals like himself and his followers, from first-time offenders, he had no trouble demonstrating his control "over an organisation which now reached out to embrace prison, mine compound and black township alike".

In fact, in some ways his status only grew, and while inmates readily made sacrifices of food, tobacco or dagga to him, the entire prison would often echo to calls of "Bayede", a greeting reserved for Zulu royalty.

Between 1900 and 1904 there was a concerted effort to break Nongoloza by means of putting him in chains, up to 25 lashes at a time, hard labour, transfers between Pretoria and The Fort, further sentences and hard labour as a result of attempted and successful prison escapes. He tried to communicate his grievances with the system to the authorities, however, the discipline he imposed on his army was equally harsh.

Suspected infiltrators were severely punished: beatings on the chest with clenched fists; eating large quantities of porridge and then being subjected to blows in the stomach; thrown up into the air in a blanket then allowed to drop on to the concrete floor; and having the front teeth removed by forcible extraction, a blow from a wooden spoon, or being cut out with a penknife.

These teeth were then added to a necklace of teeth that it's believed Nongoloza wore, Van Onselen records.

Meanwhile, crime in the burgeoning town escalated. New recruits to the mines, replacing the Chinese labourers returning to their homeland, were soon introduced to Nongoloza's Ninevites. The recession of 1906 to 1908 just added to the gang's pool of recruits, which by now stretched from Benoni in the East Rand to Potchefstroom, some 400 kilometres southwest of Joburg, in North West province.

It was estimated that by 1912 Nongoloza's "expanding criminal army" had close to "1 000 Zulu, Shangaan, Swazi, Xhosa and Basuto adherents".

Life imprisonment

In March 1909 Nongoloza received life imprisonment with hard labour for theft, stock theft, five counts of housebreaking and the attempted murder of an elderly white person. He had been sent to a prison in the small town of Volksrust, on the border of KwaZulu-Natal, where a small group of Ninevites operated. He escaped from this prison, and committed the crimes he was convicted of in March.

On his arrival back in Pretoria prison, the cells reverberated to the shouts of "Bayede" from his followers. "Back in personal control of his still expanding empire, Note and his immediate followers recommenced their struggle with a vengeance," says Van Onselen.

Nongoloza and several other "judges" sentenced the head warder and a warder to death and having his two front teeth removed, respectively. A distraction in the washrooms was unable to dislodge the head warder from his office, but the warder's resistance resulted in a hammer blow to his head, leaving him unconscious for three weeks.

Nongoloza's troops were equally active outside of prison, killing two policemen and a miner.

It was at this point that the state started linking these murders, and realised "the full extent of Nongoloza's empire, and of the fact that it embraced prison, compound and township alike".

Jacob de Villiers Roos

Just when the system seemed unable to contain him or to break him, "the Transvaal prison system was placed in the care of a skilled administrator with a genuine desire for penal reform - the remarkable and talented Jacob de Villiers Roos".

As proof of how committed to reform Roos was, Van Onselen states that between July 1900 and September 1904 Nongoloza had received 160 lashes, while between 1905 and 1912, a longer period, he only endured another 10 lashes.

Roos started with modest reforms in 1908 as director of prisons. But once he was appointed secretary for justice and director of prisons in the new government in 1910, he made several dramatic changes.

He reduced several long-term sentences. This meant that Nongoloza had his life sentence reduced to 15 years, with hard labour. He convened a special conference of prison superintendents to consider the Ninevites. Out of this came a recommendation for a single cell system, with a separation of different classes of prisoners, and the replacement of black warders with white warders.

And, most significantly, he put a "sympathetic white", warder Paskin, who was fluent in Zulu, in sole charge of Nongoloza. Roos gradually replaced "isolation with enquiry, deprivation with dialogue and lashing with listening", notes Van Onselen.

Then, over the next three months, the unthinkable happened: "Roos slowly nudged Note towards acceptance of the startling idea that he call a truce to his war of 25 years, renounce his title as 'King of the Ninevites', disband his increasingly anti-social organisation and consider working for the new state."

Prison release and jobs

On 27 December 1912, Nongoloza turned. He called in Roos and made his statement to him, through Paskin, indicating "his willingness to work as a warder for the new prison administration".

Paskin confirms this in his report: "When he says he has given up the Nineveh business and issues no orders I absolutely believe him. I think he is a Zulu who prides himself that he only has one word and as he gave his word to the director of prisons that he was not and would not issue any orders, I think his word can be unreservedly taken."

In Nongoloza's own words: "As I told you and promised you before, and word once given may not be broken, I have definitely given up the organisation."

He was released from prison on 24 December 1914 and instructed to go to work on the East Rand where he was to assist in dismantling the Ninevite network at the Cinderella Prison. He succeeded in "blunting" the Ninevites in this prison.

He was then moved to the Durban Point Prison where he succeeded in denting but not eradicating the organisation, says Van Onselen.

Roos felt that Nongoloza wouldn't achieve more than this, so he was moved to Swaziland, where a small plot of land was purchased for him. Now in his 50s, he became "a respectable member of his community, and a leader amongst native agriculturalists". He remained in Swaziland for six years, but in the seventh year Nongoloza asked if he could return to the Transvaal.

He was set up as an orderly in the Weskoppies Mental Hospital, close to the Pretoria Prison. He was now 57 years old and he settled into the new job but kept to himself, proving to be irritable and difficult when he was not given his regular supply of or marijuana or dagga.

He made friends with another orderly, Jim Mailula, and together they would visit the nearby shebeens. They would entertain women, and drink and smoke dagga together. But when he needed more money for this recreation he slipped easily back into old habits. He would stop gangs of "houseboys", and after telling them who he was, would extract money from them.

One afternoon at the hospital, carrying a bag of cabbages and pumpkins from the hospital gardens, which he planned to exchange for beer or dagga, he was stopped at the gate by a new employee who asked to see what was inside the bag. This elicited an angry outburst and he threatened to kill her.

Within days he was transferred to the Premier Diamond Mine at nearby Cullinan, to take up the post of compound policeman.

But his past came with him. He managed to "instil so much fear in the other compound policemen that he had to be moved to a position which made greater space for his formidable personality". He was moved to the mine store, where he managed to instil fear in the larger population, but he stayed for a year.

Back to prison

But then an incident happened which unravelled his new life - he grabbed and raped a 16-year-old girl who was walking past in a group, coming from church.

On 13 May 1930, at the age of 63, he was declared "an habitual criminal" and given "the indeterminate sentence". Nine days later he was transferred to Barberton Prison in Mpumalanga.

He appears to have been a model prisoner. He spent 10 years in prison, spending his days weaving baskets. He was released in October 1940, and was put on the train to Pretoria. But if he was quietly enjoying the ride, his reverie was broken at the Belfast station - the platform resounded to the roar of "Bayede" and "Ngwenyama" - the king who rules, and the lion. A dozen Ninevites, some elderly like him, were calling for him to once again lead them as Ninevites.

He was given a job as guard at Pretoria General Hospital, but later moved on to night watchman at a soft drink bottling company in Pretoria. He left this job and during 1946 and 1947 drifted around Marabastad, in the Pretoria CBD, with a bottle of liquor in one hand, often accompanied by a much younger woman.

A few months later he was admitted to the Pretoria General Hospital suffering from advanced tuberculosis. Three months later, at the age of 81, he died. Nobody claimed the body and he was buried as a pauper. On 13 December 1948 his body was lowered into a shared grave, number 1438, in "native section D", of Pretoria's Rebecca Street Cemetery.

Nongoloza had spent some 24 years in prison, and received over 170 lashes to his body.

Nongoloza's legacy

If he were still around, Nongoloza would be intrigued to know that he is still very much alive in South African prisons. Three notorious gangs - the 28s, the 27s and the 26s - each trace their origins to Nongoloza. Each gang has evolved a different myth of how Nongoloza came about, attaching significance to different parts of the tale.

The role of the 28s, says Jonny Steinberg in The Number, is to fight for better conditions for inmates on behalf of all three groups. The 27s have the function of keeping the peace, or wreaking revenge when blood is spilled. The 26s, on the other hand, are to acquire wealth through cunning, to be shared among all three groups. Nongoloza's demarcation of different roles in the gang, like magistrates, still exists.

Says Steinberg: "And as the memory of the great outlaw was passed from mouth to mouth, across the country and over the generations, so his life became myth, and his myth became law."

Van Onselen puts Nongoloza and his legacy in perspective - he should be seen as "a social bandit who led a legitimate form of black resistance against the process of proletarianisation by directing a campaign of robbery and violence against the more powerful and wealthy in the country - the whites".

Van Onselen ends his 54-page book by asking: "Who made Nongoloza?" The answer seems obvious.

Source: joburg.org.za

#Nongoloza #kingoftheNinevites #KwaZuluNatal #thesmallmatterofahorse #borninzululand #Bergville #Tugelariver #MzuzephiMathebula #CharlesvanOnselen #Harrismith #houseboy #agroomwithfourgentlemen #Turffontein #KlipriviersbergnatureReserve #highwayrobbers #InkoosNkulu #Witwatersrandslumpenproletarianarmy #landdrost #UmkosiWezintaba #RegimentoftheVills #LordMilner #30lashes #dagga #Bayede #TheFort #Nongolozasempire #JacobdeVilliersRoos #warderPaskin #fluentinZulu #DurbanPointPrison #WeskoppiesMentalHospital #PretoriaPrison #JimMailula #Premierdiamondmine #BarbertonPrison #Marabastad #tuberculosis #number1438grave #28s #the27s #the26s #JonnySteinberg #TheNumber #Nongolozaslegacy

Comments